The Federal Constitution

How the Constitution is interpreted, and who the interpreters are, has life-altering, even fatal, consequences for people.

Hello Fellow Explorers,

We cannot understand our nation’s criminal law and the criminal legal system, let alone our republic, without understanding our Constitution. Even more, we need to understand how it is interpreted, and by whom, given the life-altering, even fatal, consequences that may result.

Consider the well-known decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) that have impacted such things as citizenship rights for Black men, voting rights for non-white people and women, reproductive rights for women, access to health care, whether and how people can be executed, the extent of police powers, etc. The list goes on.

The federal Constitution is a gargantuan topic, to be sure; however, we will focus only on a few lesser-known components that are both relevant and vitally important to understand. In addition, it is important to remember that we will only address the federal Constitution and not the constitutions of the fifty states, which differ in varying degrees. That discussion will come in later editions.

The federal Constitution

The federal Constitution was drafted in 1787, ratified in 1788 by nine of the thirteen states, and has been in operation since 1789, when the first Congress was seated. For my Rhode Island readers, and perhaps unsurprisingly to all, “recalcitrant Rhode Island finally joined the Union” in 1790, the last state to do so. (Quote from Chief Justice of SCOTUS William Rehnquist).

The Constitution had a preamble and seven articles. Today, the Constitution has twenty-seven ratified amendments, including the ten amendments that constitute the Bill of Rights.

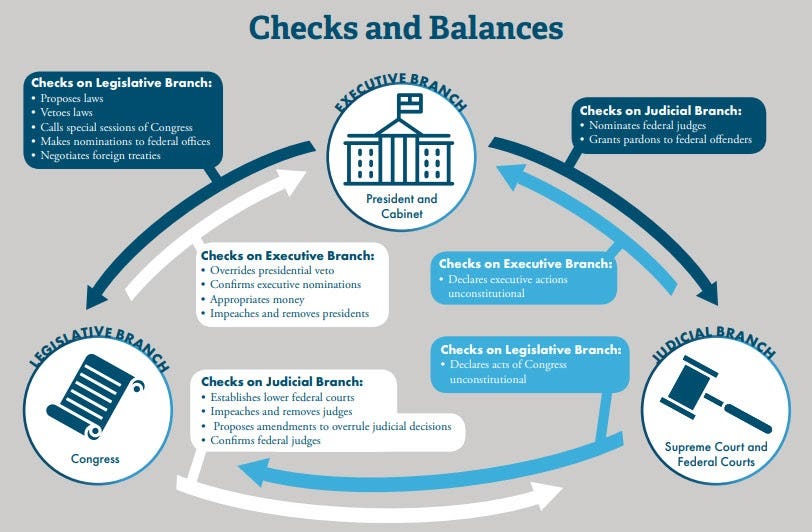

In the first three articles of the Constitution, the specific powers of each branch of government are laid out, giving each branch mechanisms to check and balance the others. Here are two refreshers.

Article IV outlines the relationship between states and between the states and the federal government. Article V and VII delineate the mechanisms to amend and ratify the Constitution. Article VI requires that elected officials “shall be bound by oath or affirmation to support the Constitution”3 and that “the Constitution and federal laws . . . take priority over any conflicting rules of state law.”4

Historical context

Many of us learned in school that the framers of the Constitution sought to: counteract the tyranny and ubiquity of the British monarchy; unionize the states to effectively defend themselves from external and internal threats; and, codify that “all men are created equal,” akin to the Magna Carta. The 55 delegates who attended the Constitutional Convention sessions became our founding fathers.5 The Constitution was ratified. The U.S. was born. The end.

But, that is a narrow, highly selective, and dangerous narrative about the Constitution. The hard truth is that the white, wealthy, landholding men that that drafted the Constitution also benefited directly and indirectly from the enslavement of African peoples at the same time. In fact, 25 of the 55 delegates enslaved people.6

In addition, the delegates and those they represented were active in the genocide and ethnic cleansing of the Indigenous peoples who lived on this land before white settlers invaded.7

The pervasive patterns of white supremacy, settler colonialism, slavery, and genocide were central to and normalized in the political, social, and economic discourse of the day. The framers employed these organizing principles to decide what and who were and were not included in the Constitution.8 Because of this, and to strike agreement with southern states, the drafters crafted a Constitution that not only allowed for slavery, but protected it in myriad ways.

For example, when the drafters of the Constitution selected the formula to calculate the population for representation and taxation purposes, they decided that African Americans should be counted as three-fifths (⅗) of a person9 and Indigenous peoples who were not “not taxed” should be excluded altogether10.

This erasure of humanity was ratified and documented in Article I, Section 2 of the Constitution. (You can learn more about that here and here).

The Bill of Rights; but, wait, where’s equal protection of law?

After the Constitution was ratified, James Madison introduced twelve additional amendments. The first ten make up the Bill of Rights (BOR), which provide or protect what are called “individual rights”:

First Amendment: Religion, Speech, Press, Assembly, Petition

Second Amendment: “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms shall not be infringed.”

Third Amendment: Quartering of Troops

Fourth Amendment: Unreasonable search and seizure

Fifth Amendment: Grand Jury, Double Jeopardy, Self-Incrimination, Due Process

Sixth Amendment: Criminal Prosecutions - Jury Trial, Right to Confront and to Counsel

Seventh Amendment: Common Law Suits - Jury Trial

Eighth Amendment: Excess Bail or Fines, Cruel and Unusual Punishment

Ninth Amendment: Rights not explicitly stated in the Constitution may exist for the people

Tenth Amendment: Any powers not given to the federal government (3 branches) by the Constitution and not prohibited for the states are “reserved to the states respectively, or to the people.”

(The Library of Congress has the ten amendments laid out for you here).

There are many, many, many exceptions, caveats, and limitations to those rights and to whom they apply.

NOTE: There is no mention of “equal protection of the laws”!

Equal protection of law arrives fashionably late

“Equal protection of the laws” (a la the Fourteenth Amendment) did not become a part of the language of the Constitution for seventy-plus years after its initial ratification.

Between 1865-68, the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments, known as the Civil War or Reconstruction Amendments, were ratified.

They added the following rights:

Thirteenth Amendment (1865): Section 1 states—“Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

Note that the Thirteenth Amendment did not entirely abolish slavery.

Section 2 gives Congress authority to enforce this amendment.

Fourteenth Amendment (1868): There are five sections to this amendment:

Section 1 granted citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States—including formerly enslaved people.

Section 1 also includes the clause “equal protection of the laws”, the meaning of which has been heavily argued about in and out of court since it was ratified.

Sections 2 through 5 primarily deal with representation in government, etc.

Fifteenth Amendment (1870):

Section 1—“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

Section 2 gives Congress the power to enforce this Amendment.

The BOR plus Amendments 13, 14, and 15 (BOR+3) In Action

The BOR+3 is primarily concerned with individual rights, but it is important to note that their meanings, protections, and applications have shifted substantially over the centuries and are still changing. In other words, at no point in U.S. history have the meanings, protections, or applications afforded by the BOR+3 been set in stone. They are written in sand.

Because of this constant (d)evolution, there is an immense amount of scholarship on this topic. In this newsletter, I focus on three key aspects of the BOR+ 3 that, in my experience, are lesser known by the general public. They are:

whose actions are actually limited by the BOR,

incorporation of the BOR to the states, and

interpretation of the BOR.

Who can and can’t do what under the Bill of Rights?

The BOR was originally intended to protect our individual rights from an invasive or tyrannical federal government. It was not intended to limit actions by state governments or private individuals/companies—something I didn’t fully understand until I went to law school.

A government actor is someone who works for the government and is given legal authority by the government to act on its behalf, e.g. an FBI agent or an official from the Environmental Protection Agency.

Contractors acting on behalf of the government may also be limited by the BOR, but that is typically decided on a case-by-case basis by the courts. This is a complicated and nuanced issue.

Here is an example to help us better understand:

In a 1999 civil rights law suit, a federal court held that CoreCivic, a private prison company, and its employee were state actors at the time of the alleged incident. During the specific incident, the CoreCivic employee was “performing job functions normally attributed to state authority, i.e. the strictly governmental authority to incarcerate people.”11

Depending on the circumstances in another lawsuit, however, the court may decide CoreCivic is not a state actor. The specific circumstances really drive the outcome. As we lawyers love to say, it depends.

You may have noticed that the above list does not include private actors, like your mom, your employer, businesses, large corporations, etc. The BOR does not protect us from other private citizens, like you and me, or corporations.

In other words, if Facebook or Twitter shuts down your account based on what you are posting, they are not violating your Free Speech rights under the BOR. They are private corporations, not government actors.

It is only when the government, or its agent, does something to impede your rights that the BOR comes into play, and even then . . . it depends.

Incorporation is not just for businesses. . .

I am embarrassed to admit that I did not know that the BOR did not automatically apply to the states until I was a 40-year-old student taking Constitutional Law. When the Bill of Rights was ratified it only applied to the Federal Government and to federal court cases. While states could include such rights in their own constitutions and laws, they did not have to do so.

When the Fourteenth Amendment went into operation in 1868, the incorporation doctrine was invented by SCOTUS. The high court applied the doctrine to determine if a protection of a right afforded through the BOR applied to state action. SCOTUS justified the incorporation doctrine through the word “liberty” and the “due process” clause in section 1 of the Amendment.

For frame of reference, the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment states:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Here’s the catch: SCOTUS did not determine that because of the Fourteenth Amendment every section of every amendment in the BOR applied to the states. Instead, it adopted “selective incorporation,” where it determines clause-by-clause in each amendment what applies to states.

In other words, each clause in each of the amendments needs to be challenged all the way up to SCOTUS for it to decide if the clause applies to the states, or not.

**Clauses are the segments between semi-colons, and sometimes even commas—like the Due Process clause in bold above.

For Example:

Let’s look at the Fourth Amendment because it is relevant to criminal law. It is also immensely important and blessedly brief:

THE RIGHT OF THE PEOPLE TO BE SECURE IN THEIR PERSONS, HOUSES, PAPERS, AND EFFECTS, AGAINST UNREASONABLE SEARCHES AND SEIZURES, SHALL NOT BE VIOLATED, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

To oversimplify things, the first clause (in all caps) was originally interpreted to mean that the Federal Government and any actor authorized by the Federal Government (described in the previous segment) could not unreasonably search and seize a person’s:

person (their body and clothes, basically),

house, or

personal effects, such as: cell phones, computers, vehicles, and every other article of moveable property.

SCOTUS, over time, developed the concept that if the Federal Government (e.g. FBI agent) was unreasonable in its search or seizure, any evidence collected could not be used against that person in court. This is called the Exclusionary Rule. (Stay tuned for more on that issue in upcoming newsletters!).

Only sixty years ago, in 1961, SCOTUS handed down Mapp v. Ohio, a seminal criminal law case. In the opinion, the Court held that because of the Due Process Clause in the Fourteenth Amendment, the unreasonable search and seizure clause applied to states. Until that decision, the states did not have to adhere to this clause of the Fourth Amendment unless it made its own laws and rules about it.

The second clause about warrants was not incorporated to the states until 1964 in Aguilar v. Texas. Yes. It’s that recent!

SCOTUS adopted a piecemeal approach for incorporation. The doctrine is still applied today. In fact, the protection against excessive fines, located in the Eighth Amendment, was only incorporated to the states in 2019 through Timbs v. Indiana.

To see more on this, check out the Legal Information Institute’s breakdown.

How is the Constitution interpreted?

Though I will address this in-depth when I write about SCOTUS later on, it is important to talk about it briefly here. The law and the legal system are human constructions that shift and change over time. Consider these three issues:

Who has the power to interpret the Constitution, and the BOR+3 within it, is profoundly influential on the ways in which the law (and our society) values our life and liberty.

How the Constitution is interpreted by those in power, especially SCOTUS, determines the meaning and reach of the rights explicitly protected by/in the BOR+3, such as protection against unreasonable search and seizure.

Interpretation philosophy also determines if SCOTUS justices believe that there are rights implied in the language of the Constitution, even if not enumerated.

As an example, the right to privacy, or as Justice Brandeis called it, “the right to be left alone,” is inferred from a number of different amendments depending on the justice’s viewpoint. But, the right to privacy is not explicitly stated in the BOR. As such, the Constitutional right to privacy and its scope are hotly debated and in flux.

Whether a justice believes the right to privacy can be validly extrapolated from the Constitution impacts many facets of our lives, such as whether women can access contraception, same-sex intercourse can be criminalized, or interracial relationships can be outlawed.

To reiterate, this is all written in sand, not set in stone. Or, as Justice Douglas wrote so eloquently in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965):

The foregoing cases suggest that specific guarantees in the Bill of Rights have penumbras, formed by emanations from those guarantees that help give them life and substance.

If you are scratching your head at this, so, too, are law students, legal scholars, and judges everywhere. What those penumbras of rights are, or even what a penumbra is, is a topic of great debate in the legal field and beyond.

In sum, interpretation of the Constitution is deeply important for all of us and it has one constant—change.

In Conclusion

As I stated at the beginning, the Constitution, its interpretation, and who is given the power to interpret it impacts every facet of our private and public lives. While that may feel disconcerting, or even terrifying, with good reason, it can also be incredibly empowering. Our voices do matter. Change is possible.

Now, please join me, dear reader, and this community to delve deeper, ask questions, respectfully disagree, and share ideas in the comments section. I hope this is the start of many conversations over coffee, dinner tables, and online!

Lastly, I welcome your feedback. These newsletters are to demystify and inform. Please let me know what is or is not working so I can make this into the most useful resource I can.

Respectfully,

Amy

Resource List:

If you want to learn more, I curated a list of resources to get you started.

Podcasts:

Constitutional, by Lillian Cunningham at The Washington Post

Civics 101, by Hannah McCarthy and Nick Capodice at New Hampshire Public Radio

“The Land that Never Has Been Yet,” by John Biewen and Chenjerai Kumanyika at Scene on Radio: https://www.sceneonradio.org/the-land-that-never-has-been-yet/

We the People, by Jeffrey Rosen at The National Constitution Center: https://constitutioncenter.org/debate/podcasts

“The Savage U.S. Constitution with Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz,” by Nick Estes and Jen Marley at The Red Nation Podcast: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/the-red-nation-podcast/id1482834485?i=1000496900243

Videos/Documentaries

Amend: The Fight for America (Netflix docu-series): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-E4TUQ4THIE

A More or Less Perfect Union (PBS docu-series): https://www.pbs.org/wnet/more-less-perfect-union/video/slavery-and-the-constitution/

The Constitution Project, a collaboration between the Annenberg Classroom and The Documentary Project: https://www.theconstitutionproject.com/films/

Constitution USA with Peter Sagal (PBS docu-series): https://www.pbs.org/video/constitution-usa-peter-sagal-more-perfect-union/

Slavery by Another Name (PBS documentary): https://www.pbs.org/tpt/slavery-by-another-name/home/

Thirteenth (documentary):

“The Beginning of the Bill of Rights,” an interview with Carol Berkin at the National Constitution Center:

Websites/Web Tools:

National Constitution Center: https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution

National Archives: https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs

Library of Congress: https://www.congress.gov/founding-documents

Library of Congress, “Documents from the Continental Congress and the Constitutional Convention, 1774 to 1789”: https://www.loc.gov/collections/continental-congress-and-constitutional-convention-from-1774-to-1789/about-this-collection/

“A brawl between Federalists and anti-Federalists, 1788”: An original newspaper article from the time, located: https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/spotlight-primary-source/brawl-between-federalists-and-anti-federalists-1788

Articles:

The Battle for the Constitution, a series by The Atlantic: https://www.theatlantic.com/projects/battle-constitution/

“The Bill of Rights: How did it happen?"“, National Archives: https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/bill-of-rights/how-did-it-happen

“The Bill of Rights: A Brief History,” by the ACLU: https://www.aclu.org/other/bill-rights-brief-history

Danielle Allen, “The Flawed Genius of the Constitution,” The Atlantic: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/10/danielle-allen-constitution/615481/

“The best books on the US Constitution recommended by Jack Rakove,” in Five Books: https://fivebooks.com/best-books/jack-rakove-on-the-us-constitution/

David E. Wilkins, “Indigenizing the U.S. Constitution” on Starting Points Journal: https://startingpointsjournal.com/indigenizing-the-us-constitution-wilkins/

Books

Akhil Reed Amar, The Bill of Rights: Creation and Reconstruction

Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist Papers

Carol Berkin, A Brilliant Solution: Inventing the American Constitution; The Bill of Rights: The Fight to Secure America's Liberties

Daniel Sjursen, A True History of the United States: Indigenous Genocide, Racialized Slavery, Hyper-Capitalism, Militarist Imperialism and Other Overlooked Aspects of American Exceptionalism

Eric Foner, The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution

Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States

Ibram X. Kendi, Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America.

Joseph J. Ellis, American Dialogue: The Founders And Us

ReVisioning American History series: https://revisioningamericanhistory.com/about/

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States

From the American Bar Association: https://abaforlawstudents.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/separation-of-powers-1.jpg

From the American Bar Association: https://abaforlawstudents.com/2018/05/01/law-day-2018-focuses-on-separation-of-powers/

Cornell Legal Information Institute “Oath of Office”: https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution-conan/article-6/clause-3/oath-of-office

This is known as the Supremacy Clause. National Constitution Center’s Interpretation of Article V: https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/interpretation/article-vi/clauses/31

National Archives, “Founding Fathers” exhibit: https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/founding-fathers

Steven Mintz, “Historical Context: The Constitution and Slavery” for The Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History: https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/teaching-resource/historical-context-constitution-and-slavery#:~:text=The%20framers%20of%20the%20Constitution,refuse%20to%20join%20the%20Union

“The Savage US Constitution with Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz", on The Red Nation Podcast with Nick Estes and Jen Marley

A More or Less Perfect Union, Episode 1 “Slavery and the Constitution”: https://www.pbs.org/wnet/more-less-perfect-union/video/slavery-and-the-constitution/

The second example is in Article IV, Section 2, which was originally called “The Fugitive Slave Clause.” Learn more here: https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/interpretation/article-iv/clauses/37

David E. Wilkins, “Indigenizing the U.S. Constitution” on Starting Points Journal: https://startingpointsjournal.com/indigenizing-the-us-constitution-wilkins/

“Private Prison Guard Is State Actor for § 1983 Purposes” in Prison Legal News: https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/news/1999/jul/15/private-prison-guard-is-state-actor-for-1983-purposes/